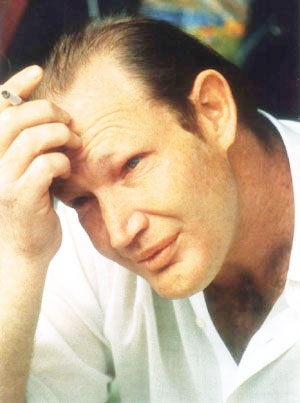

When

Kerry Packer published the first details of

his World Series Cricket in his news magazine

The Bulletin almost 30 years ago, his minions

seemed to have hit a piercing high C on the

hyperbole register. Oddly, perhaps, the hype

has stood up well' World Series Cricket was

"most imaginative" and very much a

"staggering coup", produced some cricket

worthy of (he description "magnificent"

and proved enough of a "boost" to

cricket to Justify a minute's silence at the

MCG on the news of Packer's death on Boxing

Day. Thirty years ago the rights to broadcast

Australian cricket were worth A$70.000 a year.

Today

the figure is A$45m (around £19m).

Today

the figure is A$45m (around £19m).

Yet this is also misleading. One of the tricks

history plays is making events appear manifest

destiny when they are actually coalitions of

circumstance and character. Geoffrey Blaine,

in his evocative history of the first century

of Australian settlement. A Land Half Won, devotes

a fascinating section to the movement for secession

of north Queensland. even producing a speculative

chronology for the colony that never was. "There

can be no discussion of a powerful event without

realising that it is like a traffic junction

where a society is capable suddenly of changing

direction," he says, "In writing history

we concentrate more on what did happen, but

many of the crucial events are those which almost

happened." The secessionist movement of

Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket did happen,

but what if it had not, which was nearly the

case?

The origins of WSC lie in two parallel ambitions.

One was Packer's desire to obtain exclusive

Test match broadcast rights, as a means of winning

cheap and popular summer content fat his Nine

Network: the other was the abiding sense of

grievance among Australian Test cricketers in

the 1970s about their paltry emoluments and

the search for a solution by the successfuI

television comedians Paul Hogan and John Cornell

when they learned of it through their friend

and wannabee players manager Austin Robertson.

Both stories contain a common enemy: the Australian

Cricket Board, which had slammed the door on

Packer and dealt grudgingly with the players'

complaints. But Packer was unaware of the players'

restlessness while neither the players nor their

allies knew that Packer had tried without success

to prise open a handshake deal between the ACB

and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

in June 1976.

The narratives might never have intersected

had Packer not headhunted Hogan and Cornell

from Seven Network three months later and even

then they might have led nowhere had the individuals

been differently disposed, it compares with

Morecambe and Wise encouraging Lord Grade to

patronise a world rugby sevens competition.

As it was when Cornell discussed some son of

independent Australian cricket circuit, Packer

instinctively upped the ante: "Why not

do the thing properly' Let's gel the world's

best cricketers to play Australia's best."

Justice Christopher Slade. in his famous High

Court judgement which swept away the 1CC ban

on WSC's signatories in November 1977. contended-

"The very size of profits made from cricket

matches involving star players must for some

years have carried the risk that a private promoter

would appear on the scene and seek to make money

by promoting cricket matches involving world-class

cricketers." But had Packer not been that

'private promoter", it is unlikely anyone

would have come up with a scheme as grand as

WSC. More likely smaller-scale private promotions

- like Jack Neary's World Double Wicket Competition

in Australia and the Cavaliers in England --

would have gone on being tolerated by the authorities

as long as they represented no perceived threat;

the alternative of going head-to-head against

a 100-year-old brand name, Test cricket, was

open to Packer only because the content it generated

could be integrated into his television schedules.

The players? Without Packer's irruption they

Would probably have continued hustling for Commercial

opportunities individually. As Greg Chappell

noted at the lime: "Players were becoming

So heavily committed to their personal promotional

pursuits that it wasn't uncommon in see half

the team race off on the eve of a Test to engage

in this type of activity.'' At the time of Packer's

entrance, too, Australian cricket was obtaining

unprecedented sums through the sponsorship of

the tobacco conglomerate Amatil which, because

of the impending ban on cigarette advertising,

was building its Benson & Hedges brand into

a big name in sports sponsorship. Belated increases

in Test fees might have alleviated some discontents.

Nonetheless, Australian cricketers' grudge

against their administrators derived from conditions

as much as pay. Flashpoint had very nearly been

reached in South Africa in March 1970 when Bill

Lawry's team exasperated, and exhausted by five

months on the road, had privately boycotted

a fifth Test agreed to by the ACB over their

heads. It would not have been surprising had

they been susceptible to inducements offered

by agents for interests other than Packer.

South Africa, in fact, coincidentally destined

to be exiled from international cricket soon

after that Fifth Test-That-Never-Was but still

warmly connected to the game in Australia, was

the likeliest source of such enticements. During

the summers of 1974-5 and 1975-6 the three Chappell

brothers. Dennis Lillee, Max Walker, Ashley

Mallett, Terry Jenner, Gary Gilmour. Martin

Kent. Alan Hurst, Dav Whatmore, johnny Gleeson

and Malcolm Francke had all visited the country,

some more than once, as part of multiple tours

by the Derrick Robins XI and the International

Wanderers; the latter were even managed by Richie

Benaud.

Future visits were made problematical by the

Soweto uprising in June 1976 and, the following

year, the UN declaration against apartheid in

spurt and the Commonwealth's signing of the

Gleneagles Agreement. But the window-dressing

merger of the South African Cricket Association

and the 'non-racial' South African Cricket Board

Of Control in October 1977 kept alive the illusion

that the game there Was 'normalising' of its

own accord, and it is probable that overtures

from Johannesburg would have been as enticing

to peeved Australian Test cricketers in the

late 1970s as they were to Graham Gooch's jaded

Englishmen a few years later. As it was, leading

South Africans were among Packer's eagerest

enlistees. But it is just possible that the

schism in the game caused by Packer prevented

a deeper schism in the game over South Africa.

If we are to contemplate life had secession

never happened, it might also be worth considering

cricket had secession continued. By early 1979

what had begun as a domestic dispute had become

an internal ion a I incident. Packer had five

dozen players on his books from six countries.

WSC had toured New Zealand, was about to lour

West Indies and would have been welcome in South

Africa. The united administrative from had crumbled.

Only England's Test and County Cricket Board

refused to deal with Packer and even it was

concerned about disruption of the forthcoming

World Cup.

There was the potential at the time for Packer

to mobilise a cricket circuit coeval with Test

cricket along the lines of Lamar Hunt's World

Championship Tennis, or to become a cricket

impresario as his pal Mark McCormack at 1MG

was to golf and tennis. Though he had not invented

one-day cricket, he essentially controlled the

patents on its night, coloured and tri-cornered

variants. Some of his men were tiring of the

routine. Even Joel Garner and Imran Khan, of

whom it made stars, later admitted to an abiding

hankering for Test cricket. "Beyond a certain

point," said Imran, "it is difficult

to bowl to brilliant batsmen or face a battery

of fast bowlers day after day simply in order

to prove one's individual worth." But Packer

had also begun investing in young players like

the promising left-hander Graeme Wood, whom

he had signed on a five-year contract, while

the South Africans would have played forever.

"To this day," wrote Mike Procter.

"I don't know why WSC disbanded so suddenly

and why Kerry Packer packed it in." To

Clive Rice it "was as if someone had taken

away my right arm".

As it was, one of Packer's chief business

gifts was not losing sight of the main game:

he had gone into WSC to obtain broadcasting

rights from the ACB; he decided he would settle

for these, with the bonus that he would control

Australian cricket's promotion and profitability

through PBL Marketing. And, though he had set

up WSC in the spirit of competition with the

official game, he was also a believer in monopoly

-which he restored when he effectively gave

the ACB back its players in April 1979. He rested

content with an imaginative, staggering, magnificent

boost and a healthy piece of the action for

himself.

Power Play in Court